Rio 2016 (3): what future for Brazil’s sports policy ?

Society

Article

Today we are publishing the third and final section of the series of articles on the period following the Olympics in Brazil.

The hopes harboured by the Sports Director of the Brazilian Olympic Committee, Marcus Vinícius Freire, of joining the World Top Ten, and of staying there, were dashed. Not only that – the improvement in the total number of medals (+2, to 19) falls far short of the expectations (around 24-25). So Rio 2016 – despite the Seleção (national football team’s) victory in the football tournament – was a disappointment overall, it must be said. So where does this leave Brazil’s sports policy?

A decada de Ouro is over! Brazil is leaving behind a "golden decade" in terms of sports events organisation: 2007 Pan American Games in Rio (5,633 athletes), 2011 Military World Games in Rio (7,000 athletes), Copa 2014 and the 2016 Olympics and Paralympics (7-18 September) in Rio. There are no more sports events of this calibre on the horizon, and the economic and political landscapes are in no shape for the State to commit to such events as it was able to do so back in the first decade of the new millennium. In light of all this, the future is looking far from bright for the sports policy.

For more than ten years now, the city of Rio de Janeiro has invested considerably in prestigious sports facilities to cater for the aforementioned international competitions.

In the run-up to the 2007 Pan American Games, the following accomplishments can be cited:

Le Maracanãzinho was particularly renovated ready for the Olympics. Leonardo Jorge/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Twelve sports facilities were built or revamped for the Olympics, nine of which thanks to public funding only, one through a public-private partnership/PPP (Carioca Arenas 1, 2 and 3), and two through private channels (the golf course and marina). It is evident that the private investments lead to private management (the kind of people practising golf or sailing sports belong to the socio-economic elite anyway). As for the Arenas, the PPP also entails private management delegation generally over a lengthy period of time (20 to 30 years). Private management means submitting to the economic interests of the operator: as such it is looking doubtful that the general public will be able to use these Arenas for recreational purposes at affordable rates.

One of the venues, the Arena do Futuro (in which the men’s and women’s teams lost two Olympic handball finals), is due to be dismantled as, because it is based on a modular design, it will be turned into four schools. But what of the other venues?

The Aquatic Olympic Centre for example, given that the Maria Lenk Aquatic Centre also exists, as well as an aquatic complex in Maracanã? Let’s not lose sight of the fact that Rio de Janeiro also boasts miles upon miles of beach at Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon, Tijuca, Bandeirantes – we could go on.

Building sports facilities fit for a forthcoming event is the easy bit. Ensuring enough funding continues to trickle in, year on year, to keep them shipshape is another matter. The climate in Rio de Janeiro might not require heating in these facilities, but it does call for air-conditioning to cool them, with temperatures averaging 25 to 30° and peaks of over 40 during the southern summers (December to March), not to mention a relative humidity level of 90%.

We have seen that the 1988 Constitution authorises the Federative Republic, States and Municipalities to draw up legislation on and develop their own sports policies. And yet, a few weeks before the Olympics kicked off, the State of Rio de Janeiro – whose only investment amounted to R$ 7 million (1.9 million euros) in the Rodrigo de Freitas rowing stadium – declared a "state of financial emergency", with the governor fearing an imminent collapse in public security (Policia Militar) health, education, transport and environmental management. It goes without saying that the sports policy is bound to be affected.

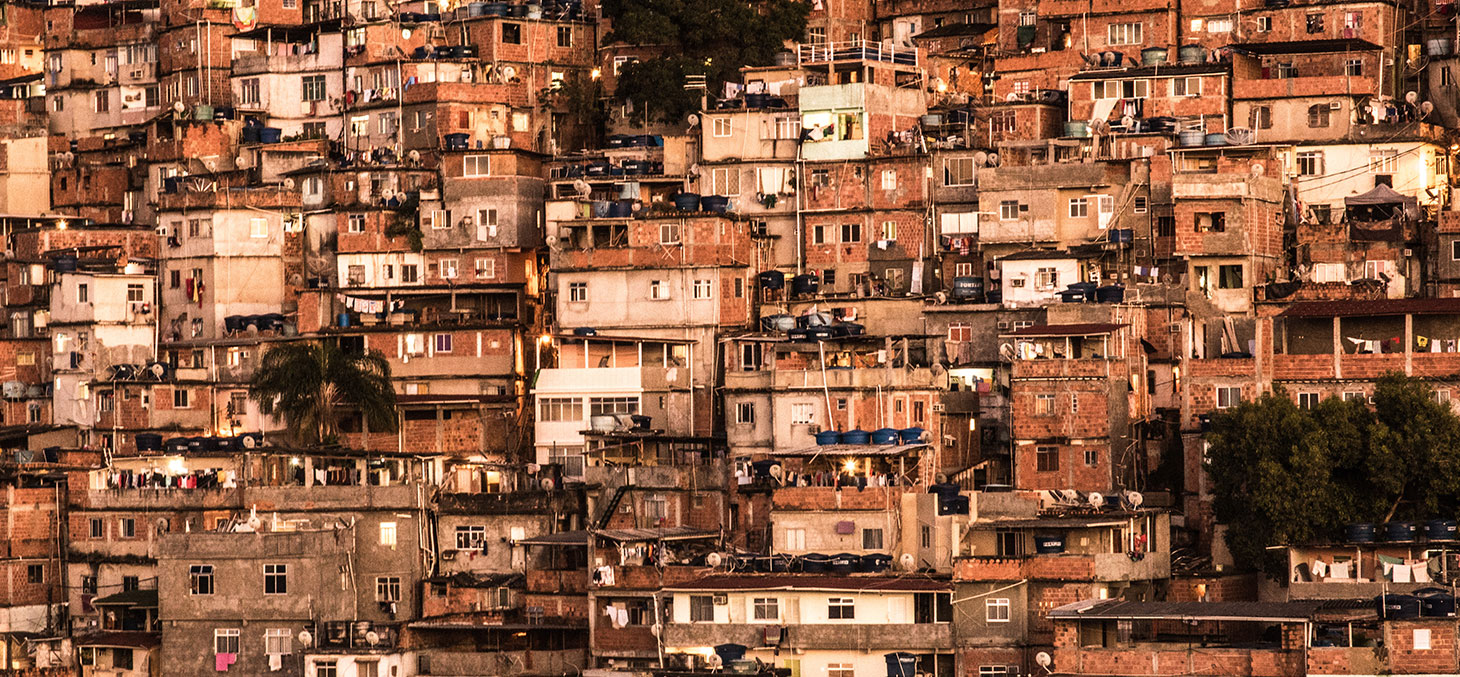

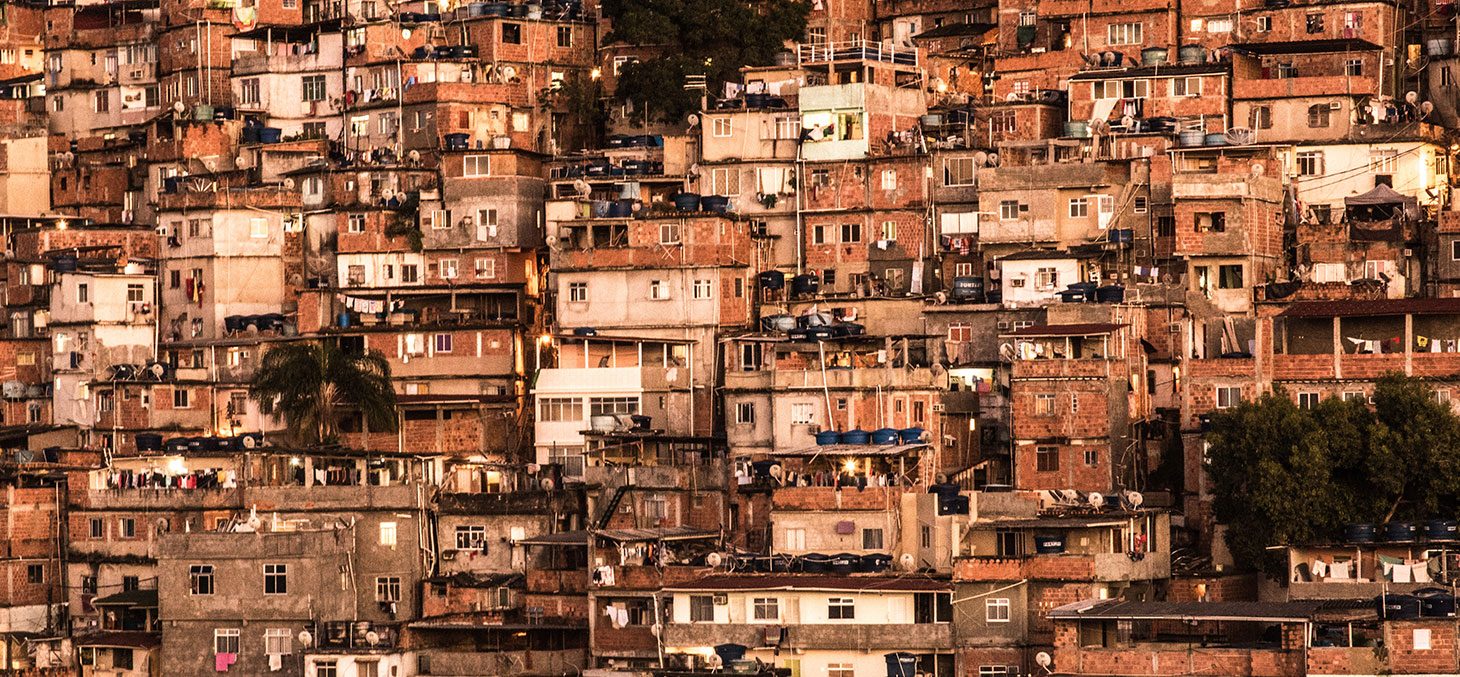

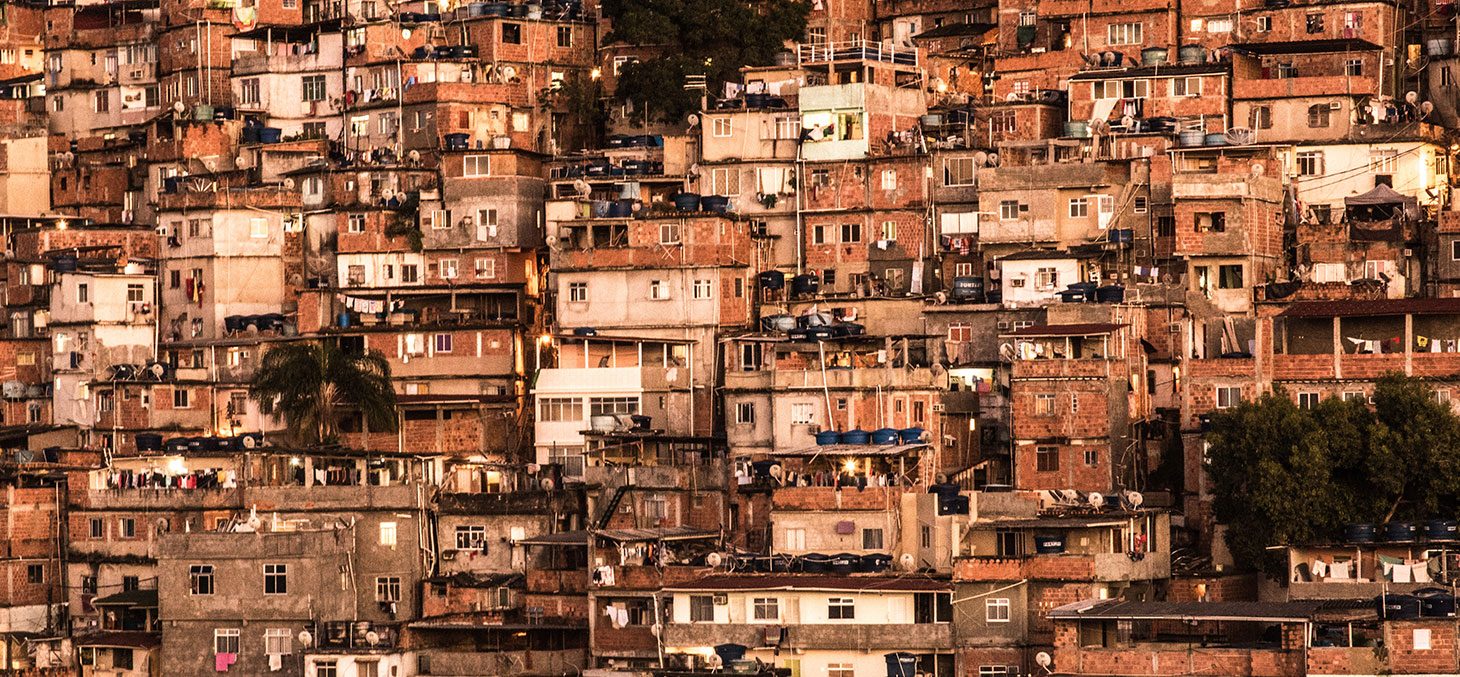

Favela in Rio. Without sufficient public funds, there is a risk that residents will sorely lack access to sports facilities. Chris Jones/Flickr, CC BY-NC

But the State of Rio de Janeiro’s decision sets a precedent that may lead to others following suit. Indeed, Brazil’s entire economy is taking a hit: falling raw material prices – on which Brazil had built its growth over the past twenty years, without factoring in the possibility of negative growth (by putting together a sovereign fund for example), or investing in promising industrial economic sectors for the future (such as the IT sector) – have plunged the country into an economic slump. The policy developed by Lula was only possible because of the positive economic context.

Today, the harsh reality is that money is hard to come by, there are no new major sports events to speak of (the Pan American Games, Football World Cup and Olympics are all in the past) and gone is any imperious need to encourage worthy sports results “at home” in preparation of future events.

The result being that that Ministry of Sport already scrapped R$ 150 million (37 million euros) worth of grants back in early June for elite sport from the 2016 Olympics preparations budget. It would come as no surprise if support wanes in the future for high-level sport, and perhaps even programmes geared towards leisure activities, citizenship and social inclusion.

It is therefore highly likely that, as is the way with the world, it will be the job of the local authorities in step with citizen’s day-to-day lives to take up sports development programmes – i.e. the Municipalities. But sports clubs in Brazil are above all organised on a private economic model, with a high buildup of capital (they own their sports facilities and must therefore service and operate them). This means that membership costs are very high as the clubs get no help through public grants.

As such, the poorest communities, those living in the favelas (slums), have zero chance of accessing any form of organised support outside of public programmes, free facilities where they can come and go as they please and NGO schemes. Sports practice, enshrined as a citizen’s right in the Constitution, risks being undermined if the economic crisis persists and drastic cuts must be made to social programmes.

The original version of this article was published in The Conversation on 2 September 2016.

A decada de Ouro is over! Brazil is leaving behind a "golden decade" in terms of sports events organisation: 2007 Pan American Games in Rio (5,633 athletes), 2011 Military World Games in Rio (7,000 athletes), Copa 2014 and the 2016 Olympics and Paralympics (7-18 September) in Rio. There are no more sports events of this calibre on the horizon, and the economic and political landscapes are in no shape for the State to commit to such events as it was able to do so back in the first decade of the new millennium. In light of all this, the future is looking far from bright for the sports policy.

What’s to become of the sports facilities?

For more than ten years now, the city of Rio de Janeiro has invested considerably in prestigious sports facilities to cater for the aforementioned international competitions.

In the run-up to the 2007 Pan American Games, the following accomplishments can be cited:

- Renovation of the Maracanãzinho indoor stadium;

- the Olympic stadium, for which the Botafogo club was delegated the management;

- the Rioarena, renamed the HSBC Arena and managed by the French company GL Events;

- the Maria Lenk Aquatics Centre, managed by the Brazilian Olympic Committee;

- the Olympic Velodrome, which had to be rebuilt from scratch for the Olympics as it did not meet the International Federation’s standards.

Le Maracanãzinho was particularly renovated ready for the Olympics. Leonardo Jorge/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Twelve sports facilities were built or revamped for the Olympics, nine of which thanks to public funding only, one through a public-private partnership/PPP (Carioca Arenas 1, 2 and 3), and two through private channels (the golf course and marina). It is evident that the private investments lead to private management (the kind of people practising golf or sailing sports belong to the socio-economic elite anyway). As for the Arenas, the PPP also entails private management delegation generally over a lengthy period of time (20 to 30 years). Private management means submitting to the economic interests of the operator: as such it is looking doubtful that the general public will be able to use these Arenas for recreational purposes at affordable rates.

Costly to upkeep

One of the venues, the Arena do Futuro (in which the men’s and women’s teams lost two Olympic handball finals), is due to be dismantled as, because it is based on a modular design, it will be turned into four schools. But what of the other venues?

The Aquatic Olympic Centre for example, given that the Maria Lenk Aquatic Centre also exists, as well as an aquatic complex in Maracanã? Let’s not lose sight of the fact that Rio de Janeiro also boasts miles upon miles of beach at Copacabana, Ipanema, Leblon, Tijuca, Bandeirantes – we could go on.

Building sports facilities fit for a forthcoming event is the easy bit. Ensuring enough funding continues to trickle in, year on year, to keep them shipshape is another matter. The climate in Rio de Janeiro might not require heating in these facilities, but it does call for air-conditioning to cool them, with temperatures averaging 25 to 30° and peaks of over 40 during the southern summers (December to March), not to mention a relative humidity level of 90%.

Sports policies on shaky ground

We have seen that the 1988 Constitution authorises the Federative Republic, States and Municipalities to draw up legislation on and develop their own sports policies. And yet, a few weeks before the Olympics kicked off, the State of Rio de Janeiro – whose only investment amounted to R$ 7 million (1.9 million euros) in the Rodrigo de Freitas rowing stadium – declared a "state of financial emergency", with the governor fearing an imminent collapse in public security (Policia Militar) health, education, transport and environmental management. It goes without saying that the sports policy is bound to be affected.

Favela in Rio. Without sufficient public funds, there is a risk that residents will sorely lack access to sports facilities. Chris Jones/Flickr, CC BY-NC

But the State of Rio de Janeiro’s decision sets a precedent that may lead to others following suit. Indeed, Brazil’s entire economy is taking a hit: falling raw material prices – on which Brazil had built its growth over the past twenty years, without factoring in the possibility of negative growth (by putting together a sovereign fund for example), or investing in promising industrial economic sectors for the future (such as the IT sector) – have plunged the country into an economic slump. The policy developed by Lula was only possible because of the positive economic context.

Today, the harsh reality is that money is hard to come by, there are no new major sports events to speak of (the Pan American Games, Football World Cup and Olympics are all in the past) and gone is any imperious need to encourage worthy sports results “at home” in preparation of future events.

The result being that that Ministry of Sport already scrapped R$ 150 million (37 million euros) worth of grants back in early June for elite sport from the 2016 Olympics preparations budget. It would come as no surprise if support wanes in the future for high-level sport, and perhaps even programmes geared towards leisure activities, citizenship and social inclusion.

Citizens' rights on borrowed time

It is therefore highly likely that, as is the way with the world, it will be the job of the local authorities in step with citizen’s day-to-day lives to take up sports development programmes – i.e. the Municipalities. But sports clubs in Brazil are above all organised on a private economic model, with a high buildup of capital (they own their sports facilities and must therefore service and operate them). This means that membership costs are very high as the clubs get no help through public grants.

As such, the poorest communities, those living in the favelas (slums), have zero chance of accessing any form of organised support outside of public programmes, free facilities where they can come and go as they please and NGO schemes. Sports practice, enshrined as a citizen’s right in the Constitution, risks being undermined if the economic crisis persists and drastic cuts must be made to social programmes.

Reference

The original version of this article was published in The Conversation on 2 September 2016.

Published on September 2, 2016

Updated on June 1, 2022

Updated on June 1, 2022

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Conversation : "Avec la guerre, changement d’ère dans la géopolitique du climat ?"

- The Conversation : "Dépenses, manque de transparence… pourquoi le recours aux cabinets de conseil est si impopulaire ?"

- The Conversation : "Et pourtant, on en parle… un peu plus. L’environnement dans la campagne présidentielle 2022"

- The Conversation : "L’empreinte carbone, un indicateur à utiliser avec discernement"